Dark matter is a form of matter thought to account for approximately 85% of the matter in the universe and about 27% of its total mass–energy density or about 2.241×10−27 kg/m3. Its presence is implied in a variety of astrophysical observations, including gravitational effects that cannot be explained by accepted theories of gravity unless more matter is present than can be seen. For this reason, most experts think that dark matter is abundant in the universe and that it has had a strong influence on its structure and evolution. Dark matter is called dark because it does not appear to interact with the electromagnetic field, which means it does not absorb, reflect or emit electromagnetic radiation, and is therefore difficult to detect.[1]

Primary evidence for dark matter comes from calculations showing that many galaxies would fly apart, or that they would not have formed or would not move as they do, if they did not contain a large amount of unseen matter.[2] Other lines of evidence include observations in gravitational lensing[3] and in the cosmic microwave background, along with astronomical observations of the observable universe's current structure, the formation and evolution of galaxies, mass location during galactic collisions,[4] and the motion of galaxies within galaxy clusters. In the standard Lambda-CDM model of cosmology, the total mass–energy of the universe contains 5% ordinary matter and energy, 27% dark matter and 68% of a form of energy known as dark energy.[5][6][7][8] Thus, dark matter constitutes 85%[a] of total mass, while dark energy plus dark matter constitute 95% of total mass–energy content.[9][10][11][12]

Because dark matter has not yet been observed directly, if it exists, it must barely interact with ordinary baryonic matter and radiation, except through gravity. Most dark matter is thought to be non-baryonic in nature; it may be composed of some as-yet undiscovered subatomic particles.[b] The primary candidate for dark matter is some new kind of elementary particle that has not yet been discovered, in particular, weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs).[13] Many experiments to directly detect and study dark matter particles are being actively undertaken, but none have yet succeeded.[14] Dark matter is classified as "cold", "warm", or "hot" according to its velocity (more precisely, its free streaming length). Current models favor a cold dark matter scenario, in which structures emerge by gradual accumulation of particles.

Although the existence of dark matter is generally accepted by the scientific community,[15] some astrophysicists, intrigued by certain observations which do not fit some dark matter theories, argue for various modifications of the standard laws of general relativity, such as modified Newtonian dynamics, tensor–vector–scalar gravity, or entropic gravity. These models attempt to account for all observations without invoking supplemental non-baryonic matter.[16]

History

Early history

The hypothesis of dark matter has an elaborate history.[17] In a talk given in 1884,[18] Lord Kelvin estimated the number of dark bodies in the Milky Way from the observed velocity dispersion of the stars orbiting around the center of the galaxy. By using these measurements, he estimated the mass of the galaxy, which he determined is different from the mass of visible stars. Lord Kelvin thus concluded "many of our stars, perhaps a great majority of them, may be dark bodies".[19][20] In 1906 Henri Poincaré in "The Milky Way and Theory of Gases" used "dark matter", or "matière obscure" in French, in discussing Kelvin's work.[21][20]

The first to suggest the existence of dark matter using stellar velocities was Dutch astronomer Jacobus Kapteyn in 1922.[22][23] Fellow Dutchman and radio astronomy pioneer Jan Oort also hypothesized the existence of dark matter in 1932.[23][24][25] Oort was studying stellar motions in the local galactic neighborhood and found the mass in the galactic plane must be greater than what was observed, but this measurement was later determined to be erroneous.[26]

In 1933, Swiss astrophysicist Fritz Zwicky, who studied galaxy clusters while working at the California Institute of Technology, made a similar inference.[27][28] Zwicky applied the virial theorem to the Coma Cluster and obtained evidence of unseen mass he called dunkle Materie ('dark matter'). Zwicky estimated its mass based on the motions of galaxies near its edge and compared that to an estimate based on its brightness and number of galaxies. He estimated the cluster had about 400 times more mass than was visually observable. The gravity effect of the visible galaxies was far too small for such fast orbits, thus mass must be hidden from view. Based on these conclusions, Zwicky inferred some unseen matter provided the mass and associated gravitation attraction to hold the cluster together.[29] Zwicky's estimates were off by more than an order of magnitude, mainly due to an obsolete value of the Hubble constant;[30] the same calculation today shows a smaller fraction, using greater values for luminous mass. Nonetheless, Zwicky did correctly conclude from his calculation that the bulk of the matter was dark.[20]

Further indications the mass-to-light ratio was not unity came from measurements of galaxy rotation curves. In 1939, Horace W. Babcock reported the rotation curve for the Andromeda nebula (known now as the Andromeda Galaxy), which suggested the mass-to-luminosity ratio increases radially.[31] He attributed it to either light absorption within the galaxy or modified dynamics in the outer portions of the spiral and not to the missing matter he had uncovered. Following Babcock's 1939 report of unexpectedly rapid rotation in the outskirts of the Andromeda galaxy and a mass-to-light ratio of 50; in 1940 Jan Oort discovered and wrote about the large non-visible halo of NGC 3115.[32]

1970s

Vera Rubin, Kent Ford, and Ken Freeman's work in the 1960s and 1970s[33] provided further strong evidence, also using galaxy rotation curves.[34][35][36] Rubin and Ford worked with a new spectrograph to measure the velocity curve of edge-on spiral galaxies with greater accuracy.[36] This result was confirmed in 1978.[37] An influential paper presented Rubin and Ford's results in 1980.[38] They showed most galaxies must contain about six times as much dark as visible mass;[39] thus, by around 1980 the apparent need for dark matter was widely recognized as a major unsolved problem in astronomy.[34]

At the same time Rubin and Ford were exploring optical rotation curves, radio astronomers were making use of new radio telescopes to map the 21 cm line of atomic hydrogen in nearby galaxies. The radial distribution of interstellar atomic hydrogen (H-I) often extends to much larger galactic radii than those accessible by optical studies, extending the sampling of rotation curves – and thus of the total mass distribution – to a new dynamical regime. Early mapping of Andromeda with the 300 foot telescope at Green Bank[40] and the 250 foot dish at Jodrell Bank[41] already showed the H-I rotation curve did not trace the expected Keplerian decline. As more sensitive receivers became available, Morton Roberts and Robert Whitehurst[42] were able to trace the rotational velocity of Andromeda to 30 kpc, much beyond the optical measurements. Illustrating the advantage of tracing the gas disk at large radii, Figure 16 of that paper[42] combines the optical data[36] (the cluster of points at radii of less than 15 kpc with a single point further out) with the H-I data between 20–30 kpc, exhibiting the flatness of the outer galaxy rotation curve; the solid curve peaking at the center is the optical surface density, while the other curve shows the cumulative mass, still rising linearly at the outermost measurement. In parallel, the use of interferometric arrays for extragalactic H-I spectroscopy was being developed. In 1972, David Rogstad and Seth Shostak[43] published H-I rotation curves of five spirals mapped with the Owens Valley interferometer; the rotation curves of all five were very flat, suggesting very large values of mass-to-light ratio in the outer parts of their extended H-I disks.

A stream of observations in the 1980s supported the presence of dark matter, including gravitational lensing of background objects by galaxy clusters,[44] the temperature distribution of hot gas in galaxies and clusters, and the pattern of anisotropies in the cosmic microwave background. According to consensus among cosmologists, dark matter is composed primarily of a not yet characterized type of subatomic particle.[13][45] The search for this particle, by a variety of means, is one of the major efforts in particle physics.[14]

Technical definition

In standard cosmology, matter is anything whose energy density scales with the inverse cube of the scale factor, i.e., ρ ∝ a−3. This is in contrast to radiation, which scales as the inverse fourth power of the scale factor ρ ∝ a−4, and a cosmological constant, which is independent of a. These scalings can be understood intuitively: For an ordinary particle in a cubical box, doubling the length of the sides of the box decreases the density (and hence energy density) by a factor of 8 (= 23). For radiation, the energy density decreases by a factor of 16 (= 24), because any act whose effect increases the scale factor must also cause a proportional redshift. A cosmological constant, as an intrinsic property of space, has a constant energy density regardless of the volume under consideration.[46][c]

In principle, "dark matter" means all components of the universe which are not visible but still obey ρ ∝ a−3. In practice, the term "dark matter" is often used to mean only the non-baryonic component of dark matter, i.e., excluding "missing baryons." Context will usually indicate which meaning is intended.

Observational evidence

Galaxy rotation curves

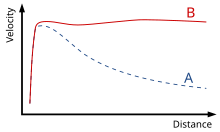

The arms of spiral galaxies rotate around the galactic center. The luminous mass density of a spiral galaxy decreases as one goes from the center to the outskirts. If luminous mass were all the matter, then we can model the galaxy as a point mass in the centre and test masses orbiting around it, similar to the Solar System.[d] From Kepler's Second Law, it is expected that the rotation velocities will decrease with distance from the center, similar to the Solar System. This is not observed.[48] Instead, the galaxy rotation curve remains flat as distance from the center increases.

If Kepler's laws are correct, then the obvious way to resolve this discrepancy is to conclude the mass distribution in spiral galaxies is not similar to that of the Solar System. In particular, there is a lot of non-luminous matter (dark matter) in the outskirts of the galaxy.

Velocity dispersions

Stars in bound systems must obey the virial theorem. The theorem, together with the measured velocity distribution, can be used to measure the mass distribution in a bound system, such as elliptical galaxies or globular clusters. With some exceptions, velocity dispersion estimates of elliptical galaxies[49] do not match the predicted velocity dispersion from the observed mass distribution, even assuming complicated distributions of stellar orbits.[50]

As with galaxy rotation curves, the obvious way to resolve the discrepancy is to postulate the existence of non-luminous matter.

Galaxy clusters

Galaxy clusters are particularly important for dark matter studies since their masses can be estimated in three independent ways:

- From the scatter in radial velocities of the galaxies within clusters

- From X-rays emitted by hot gas in the clusters. From the X-ray energy spectrum and flux, the gas temperature and density can be estimated, hence giving the pressure; assuming pressure and gravity balance determines the cluster's mass profile.

- Gravitational lensing (usually of more distant galaxies) can measure cluster masses without relying on observations of dynamics (e.g., velocity).

Generally, these three methods are in reasonable agreement that dark matter outweighs visible matter by approximately 5 to 1.[51]

Gravitational lensing

One of the consequences of general relativity is massive objects (such as a cluster of galaxies) lying between a more distant source (such as a quasar) and an observer should act as a lens to bend the light from this source. The more massive an object, the more lensing is observed.

| This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Metasyntactic variable, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. |